1 days ago · 8 min read · Systems Thinking

Reading Is Necessary; Reading Is Not Enough

Almost everyone has a book, teacher, or story that was pivotal to the major success of their life. This begs the question, why?

In 2017, I took on the personal challenge of reading fifty-two books with at least of 200 pages in the year, making for 10,400 pages to cover in 8700 hours (one year). That left me with a little under 45 minutes per page, which sounded reasonable (spoiler: it wasn’t).

In fact, with all the other living one must do, you only end

up with a few hours per day, leaving you closer to 700-1200 hours. (2-3 hours per day * 7 days per week * 52 weeks per year.)

This left me with around 6 minutes per page in the best case. So, I buckled down, read non-stop, and I learned almost nothing.

Necessary, But Not Sufficient

Reading is necessary to long-term, general success. Sometimes we get lucky, we have inside knowledge, or we’re in the right place at the right times, or have an unfair advantage against the competition that leads us to temporary success. But this success can’t last forever, meaning you’re fighting a losing battle. You need to learn general strategies that will let you survive a variety of situations you haven’t already experienced. By definition, you can’t know what you haven’t experienced, so you need to learn it from others.

Imagine someone at the top of their field. Say, a stockbroker trading

and making millions or even billions per year. Sounds like the dream,

right? Wrong. That person’s strategies are more than likely

optimized for the market they’re currently in, and if it changes, in-all

likelihood they’ll be so optimized for the previous market that

they’ll crash and burn. Now imagine if they had been in the top 20-50%, not making the most

money, but operated in a way that left room for okay performance in any

market, which would let them ride the tides of change? They might not be

number one, but they’ll also much less likely to be a zero.

While reading is necessary, it isn’t sufficient for success. Look at my story, I read fifty-two books and I didn’t learn or correctly remember a damned thing. The knowledge passed through my brain like the wind through the trees because I didn’t encode the information in my brain.

Reading is only the first step to the process of learning, and without an understanding of it, you will waste a great deal of your effort on activities that don’t make you wiser 1.

Mental Models, Success Quantified

What is sufficient? For our purposes, sufficient is any strategy that either:

Doesn’t prevent you from trying another; i.e. it doesn’t ruin your life or kill you, or;

Is close to guaranteed to get you the result you want; i.e. its 80%-100% likely to get a positive outcome

To try and find these strategies, we can talk about how humans learn, the statistics of successful people, and a lot of other topics. The former could be useful because it gives us the first principles 2 necessary to start from nothing with a new idea for success.

The rest only give us a shallow truth. Either what was necessary on average, but not sufficient for success, or what lead a single individual/small group of individuals to success in their specific circumstance. These things are all necessary for success, but they are not a promise or a strategy to get there.

What is sufficient for success is mental models — or systems of thought — that help us achieve what is necessary and protect ourselves from undue risk. Mental models allow us to take shortcuts in our thinking when we need to react quickly, or when we’re dealing with a complex situation where we don’t have the whole picture (i.e. real life). They’re our maps for life.

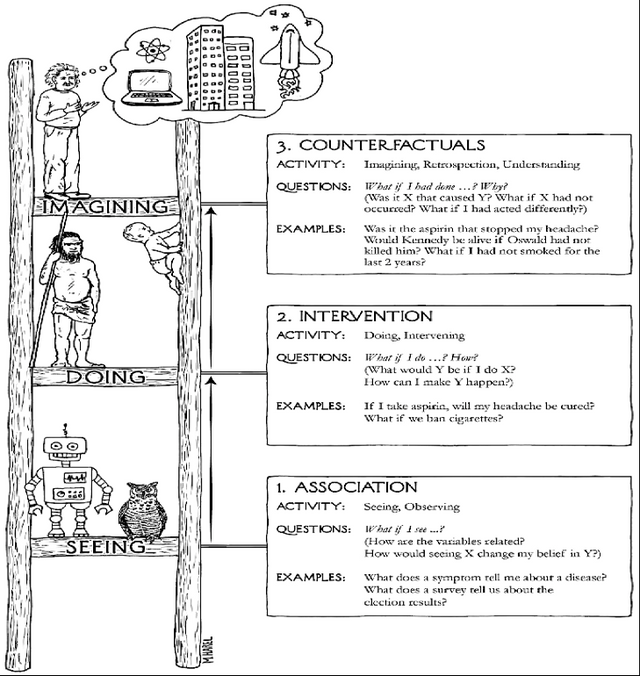

In fact, mental models are what experts believe differentiate us from a lot of other life on earth. The process of purposefully designing mental models seems unique to us, for now. For our purpose, we’ll call this process the causal ladder, or the steps to wisdom.

The Causal Ladder

Our ability to interact with the world to gain knowledge and remember what caused it is not unique — most developed forms of life can do this — and it’s sometimes called association, the bottom rung of the ladder. It’s the act of observing the world around us, what happens, where it happens, when it happens and making associations about what effects what. This helps us, and most other life, understand that what usually happens, in what order, and whether it’s good for us or not. It’s another human eating something and getting sick and warning you about eating it. This is no different from reading someone else’s book, or the act of listening to the story of someone else’s experiences to help you draw a better map of the world.

The second rung of the ladder, intervention, is unique to the most developed forms of life, including us, the great apes, man’s best friend the dog, and other mammals. It’s the cognitive ability to ask “what if I do…” questions, and then do it to the world to try them out. This ability lets us use our own experience as a tool for learning what works, what doesn’t, and whether we should keep doing it. This is the act of building mental models through continuous feedback. Every time we intervene in the world, watch what happens, and make associations, we have the potential of becoming wiser.

The last rung of the ladder, counterfactuals or imagination, is the ability that seems to be unique to humans. It’s the ability to imagine what could have happened. It’s the ability to use a mental model to replay events with different variables to get a rough idea of alternative outcomes. It’s a young hunter gatherer imagining if the hunt will fail if he only takes 3 men instead of 6, and tweak that number in his mental model until it seems plausible.

This ability to replay history or potential futures in our heads with different events and imagine different outcomes is our secret to success. With strong mental models of the world, we can replay them out with different variables and events to try and select the most desirable path.

So, with a basic understanding of the our ability to…

Learn through our senses to build rough mental models

Intervene in the world, get continuous feedback, and improve our mental models

Replay our mental models with different variables and events to get an idea of different results

…we can try to succeed in life without taking risks that will ruin us, or worse, kill us.

Taking Reading All The Way

With a basic understanding of the causal ladder, let’s loop back to our topic de jour, reading. Reading is not sufficient, because reading is only the first rung, and because our brains are notoriously good at ignoring information (we almost always lose information immediately after sensing it, otherwise we’d go nuts with sensory overload)3.

So what do we do about this? Well, it’s simple: go up the ladder.

If we read or listen to a chapter of a book, listen to an expert’s opinions from study, or experience something first-hand and find that the knowledge to seem useful, we must move up the ladder of causation to rung two, intervention. We need to do something with it as soon as possible (before bed!), and the most important thing to do is externalize it outside of memory. Write it down, record it in a notebook, zettlekasten, or other format, teach it to someone. The better the externalization is for recall, how accurate it is when you come back to it, the better your learning will be. Now you can stop thinking about it for now, and not need to devote energy and focus to committing it to memory, leaving your brain ready to improve your mental models.

Then, when you return to it at a later date, either during periods of reflection or at a moments notice when it comes to mind as being useful, you can start over at rung one, and start making associations to try and construct a useful mental model for the situation. This association will allow you to move up into rung two once more, and take the final step to rung three, counterfactuals. With the ability to perfectly recall externalized knowledge, make associations and construct a valid mental model of the circumstances, you can adjust your mental model and imagine the result without having to act it out. This way, you can get an idea of what approach is most likely to have a good result.

Without the act of experiencing or observing, then the act of intervening, and our ability to imagine scenarios where we intervene, we do not learn, we do not improve our mental models, and we do not succeed and thrive. So, if you aren’t the type to do, it’s time to lift your leg off the first rung and move it up to the second.

Footnotes

wiser; the intersection of knowledge and experience to create mental models that lead to general success over time. ↩

first principle; a foundational statement assumed to be true, that can’t be deduced from any other within that system, which all systems like it must be built from; see this video (keep in mind that while this is Elon Musk, and I do dislike Elon Musk, I can attest this is a general strategy that is definitely working for him and a lot of other innovators throughout history). ↩

details on the faultiness of our brain in encoding sensory input is explained in detail in The Organized Mind, which contains a plethora of further references ↩